Mid-Year Review Statistics

Real Estate Statistics

Statistics can be an enormously valuable tool for assessing the conditions and trends in the real estate market. However, they are also among the most misused, misquoted and misunderstood "facts" we are bombarded with. The only honest purpose for market statistics is to provide reasonably unbiased information for those trying to make decisions regarding the purchase, sale or ongoing ownership of real estate - typically one of the largest financial investments of one's life.

Long-Term Median Home Sales Price Trends: San Francisco, California, U.S.

The 1st quarter of 2014 saw a big spike in median home sales prices in San Francisco.

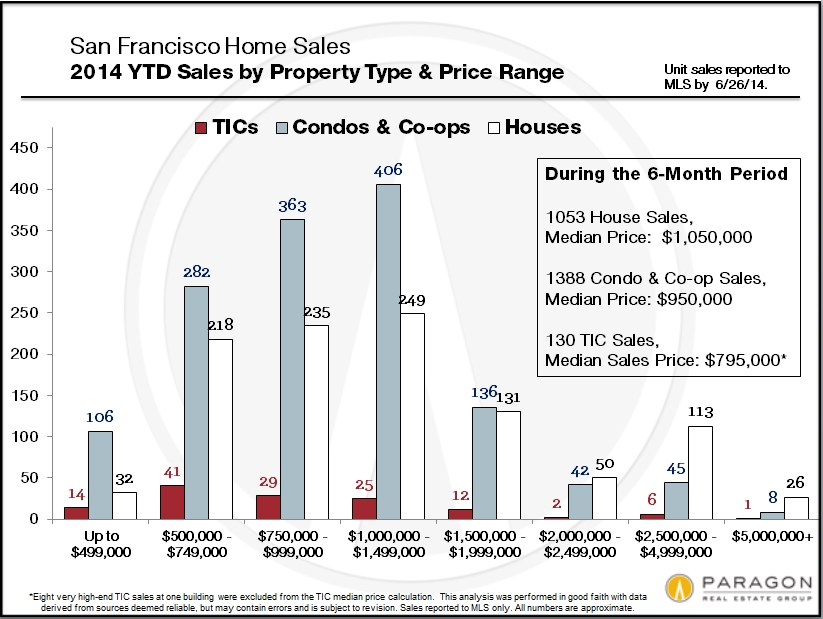

San Francisco Home Sales by Property Type & Price Range

Mortgage Interest Rates 1981 - 2014

The market appears to have adjusted to the bump in rates that occurred in mid-2013. Rates are still very low by any historical standard.

The problem is that most market analysis is provided by those who want to convince you to do something (for their own financial benefit); or those fiercely attached to one position or another - the most common being either unrelenting optimism or unrelenting pessimism; and/or those not qualified to interpret the data in the first place. Whether delivered by real estate agents, so-called pundits, analysts, reporters, bloggers, special algorithms or the guy who lives next door, all these situations often lead to the improper use of statistics.

One needs to know a specific market inside out, first to carefully vet the data for statistical flaws, outliers or anomalies, and then, standing back to look at the larger picture, to be able to intelligently interpret what it appears to signify. Having a sense of the longer-term cycles in financial and real estate markets is also helpful: markets neither go up forever or down forever -- it's amazing how often this simple fact is forgotten in the drama of the moment.

Rule 2: Average and median statistics are generalities. They often fluctuate up and down in the short term even in stable markets and price statistics are often affected by other factors besides changes in value, such as seasonality, available inventory, financing conditions, buyer profile and significant changes in the distressed-property or luxury home market segments. In San Francisco, every month sees a relatively small number of relatively unique properties sell. Median and average values often disguise an enormous disparity of values among the underlying individual home sales in the data set, and how they apply to any particular property is impossible to say without a specific comparative market analysis (CMA). To value a specific property, an analysis crafted to its exact location, condition, circumstances and amenities, is required.

Rule 3: Any definitive trend will be reflected over the longer term and in more than a single statistic, i.e. not just median price, but also dollar per square foot, months supply of inventory, percentage of listings accepting offers, days on market, and so on. Even then, it can be difficult to read the tea leaves of exactly what is happening or starting to happen on the street. Especially since closed sales data is typically 4 to 8 weeks behind the time offers are actually negotiated.

Rule 4: No one knows the future. Recent studies* suggest that the confident predictions of financial market pundits and experts are wrong 50% of the time - or more. Generally speaking, you would do as well or better just flipping a coin: Think of the years of pundit projections prior to the 2008 financial and real estate markets meltdown. Or here's another example: Robert Shiller, who helped develop the respected S&P Case-Shiller Home Price Index (and the complex algorithm behind its calculations) and is certainly one of the most often quoted financial and real estate markets economists in the country, stated in March 2012 that the U.S. homes market was probably still headed down, and that we may "never in our lifetime see a rebound in these prices in the suburbs." Since then the market has gone through a huge recovery - the market actually started to turn in 2011 - with values up 20% to 40% virtually everywhere as of September 2013, according to his own Index. That is, he could not have been more wrong. This is an excellent example of an "expert" who became attached to the anti-optimism position for which he became famous in 2008.

At Paragon, we are not immune to the failings that afflict other analysts and commentators, but we try our best to provide straightforward information regarding market conditions, with as much detail and context as possible, so that you can make your own informed decisions. 99% of our focus is on San Francisco and the Bay Area and we don’t believe anyone performs the amount of analysis we do regarding the area’s real estate. None of our charts are created automatically by computer: all the data is personally investigated and vetted for anomalies before being charted. When we do make tentative predictions of future trends, it is based upon what appears to us to be overwhelming supply-and-demand conditions and decades of experience in San Francisco Bay Area real estate. (But please see Rule 4.)

* “Why Do People Pay for Useless Advice? Implications of Gambler's and Hot-Hand Fallacies in False-Expert Setting”, by Nattavudh Powdthavee and Yohanes Riyanto, Institute for the Study of Labour, May 2012: Referenced in The Economist in their June 9, 2012, Buttonwood column titled "Not So Expert." The issue was also addressed in the September 2, 2011 issue of the same magazine in an article titled "The Perils of Prediction: Adventures in Punditry" regarding the Good Judgment Project. These articles can be read on the Economist website (subject to being a subscriber).